The End of the Great Resignation Appears To Be in Sight

Last summer, many expected that previously displaced workers would jump right back into work when enhanced and extended unemployment benefits expired. But for a handful of reasons, including fear of COVID exposure and large cushions of accumulated savings, many remained out of the labor force, especially those previously employed in low-paying sectors such as leisure and hospitality and retail, which typically involve high levels of face-to-face contact.

Since then, however, the cost of living has steadily increased as inflation pressures rise, inflated household savings have returned to lower pre-pandemic levels, and many other government stimulus measures, including most recently the monthly child tax credit payments, are long gone.

For many, the luxury of remaining out of work to avoid or recover from COVID or to care for loved ones is fading.

The end of the great resignation appears to be in sight as displaced workers are returning to work. The labor force participation rate reached 62.2% as almost 1.4 million people re-entered the labor force, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ latest report, its highest rate since March 2020. Surprisingly, the overall labor force participation saw a boost from those age 55 and older — a demographic that has been believed to be less likely to return to work during the pandemic as stock market gains and skyrocketed housing valuations boosted wealth and allowed many to opt for early retirement.

Still, the rate lingers meaningfully below its pre-pandemic level of 63.4%. With more people looking for work, the unemployment rate ticked up to 4% from 3.9% in December 2021, even as the number of people employed grew by a whopping 1.2 million over the month.

To be sure, some of these notable changes were due to revisions in the household survey to update the age distribution of the population, yet the broader picture reflects a very tight labor market. Nonfarm payrolls grew by 467,000 positions in January, much more than expected given the rapid spread of the omicron variant. Moreover, revisions to data from August through December 2021 added 817,000 positions, suggesting that the great resignation was already losing steam late last year. The revisions were made using more precise quarterly payroll data that are lagged and as a result take some time to be incorporated.

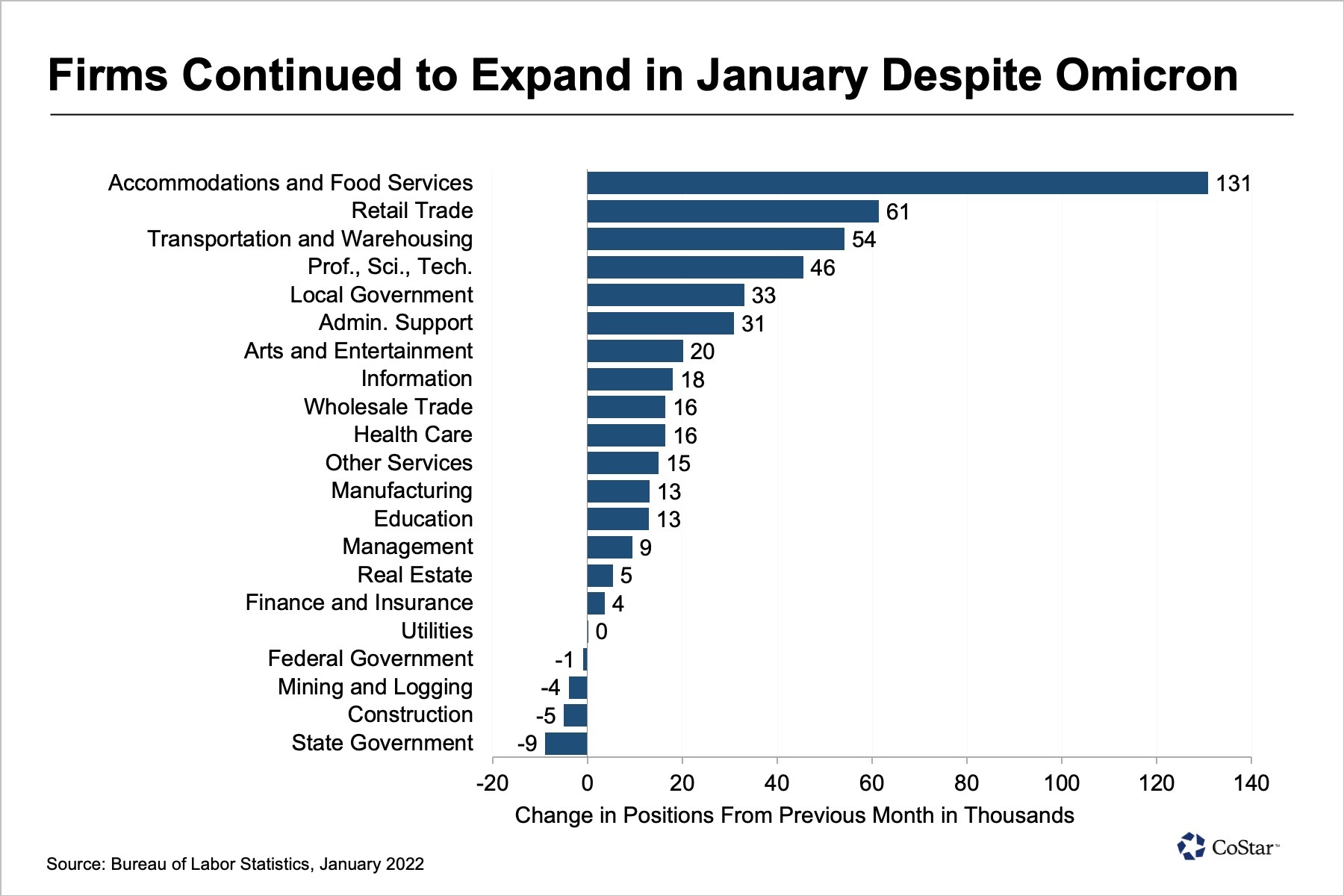

Amid widespread reports of difficulties finding qualified candidates, firms that hired for the holidays apparently decided on the path of least risk and kept staff through January, rather than letting them go after peak demand as they might have done in typical years when the labor market was more fluid. For example, hotels and restaurants added 131,000 positions and shops added 61,000 positions, but only on a seasonally adjusted basis. In typical years, January is the month when many seasonal employees are laid off after strong hiring for the holiday season. Because more firms kept their workers on staff rather than letting them go this year, the numbers show solid hiring in comparison to what was expected. In unadjusted terms, those two subsectors lost about 690,000 positions, far fewer than the average of 860,000 lost in the five years prior to COVID.

Similarly, seasonal impacts are visible in the transportation and warehousing sector, which added 54,000 positions, seasonally adjusted, while actually losing 315,500 jobs after the holiday season, fewer than in typical years.

Altogether, job growth is expected to remain elevated throughout the year as workers re-enter the labor force. There are still 2.9 million fewer nonfarm jobs than in pre-pandemic days and evidently 10.9 million job openings remain unfilled, according to a separate Bureau of Labor Statistics report. That’s a record high and roughly 50% higher than the number of job openings prior to the pandemic. This brings the ratio of unemployed workers to open positions down to 0.6%, a record low in the series history that goes back to 1982 — a challenging environment for hiring managers.

As a result, competition for labor over the past year has been intense, especially in those industries where face-to-face personal interaction is critical, and firms have had to boost wages to attract much-needed workers. This has been especially true for the hospitality industry, where low-wage jobs have been largely eschewed by COVID-fearing workers who could replace lost wages with generous stimulus payments. Wages in that industry climbed by 13% over the year in January, much faster than any other industry sector.

But wage gains have become far more widespread than affecting only those at the lower end of the pay scale. The largest month-over-month increase in wages was the 1.3% increase for workers in the information sector, which include tech workers, media companies and software publishers — think Google, CNN and Zoom. Similarly, workers in the professional and business sector, as well as those in financial services, saw month-over-month wage gains of 0.8%, while pay for leisure and hospitality workers barely budged.

This recent acceleration in wage growth of high-skilled workers illustrates the spread of competition for labor at all pay ranges, as employees are now more in control than ever before of choosing work situations that suit their preferences. The potential spillover of wage increases into price hikes is on everyone’s mind, not the least of which is the Federal Reserve as it plans for rate hikes in future months. So far, it has given no indication of a faster timetable than four quarter-point increases this year, but the situation remains fluid as more data arrives.

What We’re Watching ….

As such, the big news of this week is likely to be found in the release of the consumer price index, scheduled for Thursday. Forecasters are anticipating still-hot inflation, with prices rising at rates not seen in four decades. The index is expected to exceed 7% with the core index rising to a rate of almost 6%. This is not the Federal Reserve’s preferred measure of inflation, but it is widely watched and could leave consumers increasingly frustrated. The University of Michigan consumer sentiment index in January hit a 10-year low, at 67.2, mostly due to inflation but also because of the spread of the omicron variant. With COVID cases now on a downward trend, and people feeling more inclined to tolerate an endemic environment, fears of infection should recede, leaving inflation as the No. 1 irritant. Luckily, it seems that, while still rising, the rate of price increases is slowing after blistering escalation in the fourth quarter. Perhaps the worst may be behind us.